A LONELY CHILD DURING THE HOLOCAUST

RACHELLE: Tell me a little bit about your artwork.

ESTHER: I think that everybody just assumes that, women especially, are painters. But that’s not just it.

I started drawing and painting like other artists. I went to school and started drawing a lot. You know, we just doodle as kids. But I got interested in other materials because my father stored leather goods – hides – in a cold room where we lived. I would go in there and play and use the leather to make clothing for my dolls. That’s probably where my happiness with making things started.

RACHELLE: You were a child in Germany during World War 2. How did this influence your art?

ESTHER: Because I was a child, I wasn’t in a [concentration] camp. They kept the women and children out. Only the men were in the camps at first.

I was a lonely child. I would play with leather, and I was a dreamer… I would pretend that things weren’t so bad. But of course, they were. We lived near Buchenwald. My father was in and out of a camp between 1938 and 1939.

For artists – just as all people – our art is what our experiences are. And they form us. I always felt like the outsider. After I left Germany and came to the US, I felt like I needed to speak out about what happened… like I was a survivor. All those things formed me and my work.

BRIDGING GAPS BETWEEN JEWISH CHILDREN AND THEIR BLACK NEIGHBORS

RACHELLE: Aside from painting and leather, are there any other mediums you like to work with?

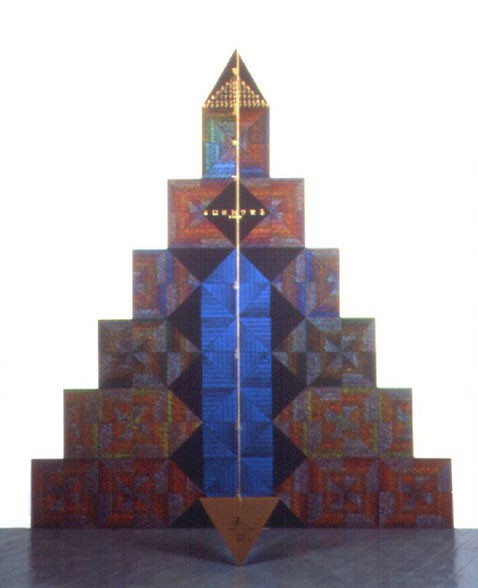

So I did a lot of painting for many many years, but as my ideas grew, it just wasn’t enough to be working on two dimensional things. I used to paint on wood because I liked the grain. Then I started cutting up the wood and making shapes. I started to make layers and layers.

I am 85 years old and I have a piece I’ve been working on for many years: a piece about babies. It’s a culmination of the way I’ve worked through the years. I never stopped myself from doing something I didn’t understand.

RACHELLE: What kinds of things have you worked on over the years?

ESTHER: Like – how to get black kids and Cheder Lubavitch kids together that didn’t hate each other. The Chabad school was right near the black ghetto. So I got the kids together.

I go from one kind of material to another as my need to speak out about something [changes]. So there I was asking the children what they each thought about the other. Recording them. Asking them questions about what each of them knew about the other.

RACHELLE: What kinds of questions did you ask the kids?

ESTHER: Are they afraid of me? If I moved in on their block would they be friends with me? They answered these questions. Then they exchanged photographs and letters with each other. And then we actually got them together at Cheder Lubavitch.

RACHELLE: What happened when the kids actually got together?

We got all the kids on the bus. I was driving my car filled with materials, and I didn’t know exactly what was going on on the bus. Certainly, going there, the African American kids were a little bit nervous.

It was really brave of all of them to do it and for all the parents to allow it. Some of the teachers and students played basketball. The girls got together right away and played with each other. And when they said goodbye they said that they hoped they would see each other again.

I’ve done things like that at other schools in Chicago, too. I’ve talked in schools that are not thought of too well. I would go in there and talk to them about how they felt about Jews.

GOING BACK TO GERMANY

RACHELLE: Have you ever been back to Germany?

ESTHER: In 2003 I did an exhibition in the city where I was born in Germany. They made a book of the catalogue in both German and English. I told them I wouldn’t have a show in Germany unless I could speak to the German children and teach them about what happened in the Holocaust.

In most countries, everybody is supposed to learn about the Holocaust. Certainly in the United States. But it doesn’t mean they do. One learns for an hour, one learns for a semester. There are different ways of learning, and I thought it would be important for me to be there.

RACHELLE: The Holocaust is such a vast topic. How did you teach the children about it?

ESTHER: We had the German children look up some of the places that Jewish people, like myself, had lived during the war before we left for Israel. Some were still alive, some had gone to Israel, and some had perished.

Germans love to keep notes and books and records. So they had records of this – of where the children had gone. So each one of them “met” their person and wrote to them. Either actually wrote to them or wrote to them through imagination.

RACHELLE: What was their reaction?

ESTHER: One of the things that was very important to me was that these students were shown films of what happened by their art teachers. One of the kids ran out and threw up. They really didn’t know. Their parents kept this from them.

This was the Russian center, so there was no religion. But these kids found a Rabbi – of course he was Chabad – and they asked him what it was like to mourn for a Jewish child. [The Rabbi taught them about modeh ani – these kids had never heard anything like that.]

ESTHER’S ART EXHIBITION IN GERMANY

RACHELLE: Can you tell me more about your art show in Germany?

ESTHER: One of the pieces that I did there was called 6 Million Almonds. It was about the luz bone: a bone in our body that doesn’t burn.

At Buchenwald, I set this up in the only building that was still standing. I had the museum director’s mother count out six million almonds and set them up in a room there. And I had the whole history and translation – from the Torah – about how we will be resurrected from that bone. (Interestingly, it’s also the bone where the tefillin gets tied.)

I made people see what it meant to look at 6 Million [of something]. Almonds. The crazy thing is that the killing gas that they used to kill the jews was also made from almonds.

RACHELLE: Was your art show in Germany well received?

People came in from all over the world. They saw the text in both Hebrew and English. In middle of the room I had these empty glass jars. And on the walls I had scrolls, from the ceiling down with pencils hanging.

People came over to drop an almond into a jar. Then they crossed out one of the almonds. Either it was somebody they remembered or a loved one.

In the next room I had a container with a slit on the top. It was for letters people wanted to send to the Western Wall. Letters from people from all over the world. And I got them to the wall.

I want to make sure you understand the research that went into this. There’s a Rabbi – he lived in New York – who had been at the [concentration] camps. Unfortunately, he had been one of the people who would gather up the ashes. He saw many, many of these small bones. So I called him. He didn’t really want to talk to me, but he just said, “Uh huh.” I also called an orthopedic doctor and he explained it to me. None of this [art show] happened without making sure that everything I put out there is truthful.

RACHELLE: Can you tell me about the some of the other pieces at your show?

Another piece I did was about immigration. It’s me in a very strange outfit, trying to fly. I have a helmet, but the strap that should be under my chin is across my mouth. My hands are buckled into my pockets and my pants have a big panel so I can’t really move that far. The outfit comes from another realm… it comes from playing around with my father’s leather.

On top of me is this machine called my Flying Machine. It’s absurd, but pretty beautiful. The machine I’m wearing is made of wood and has propellers on it. It’s about how we tried to get into Israel, and we couldn’t. They wouldn’t let us in.

The other one is Ten Children. I worked with a recording student to record the cry of a baby. We made a kind of song out of the cries. It’s been documented that all babies’ cries are the same.

We are taught that all babies come into this world already knowing so much Torah. But when the angel gives them a parting touch on the lips, they begin to forget. So let them forget hate. This piece is about forgetting hate.

RACHELLE: What do you feel is your main message to send to the world?

ESTHER: What I’m trying to do is erase hate. Today there are so many books and magazines, but the possibilities of what you can do and say has become very political. We artists, however, have captive audiences in museums.

Psychologists say that children don’t feel the emotion of hate until they are 3 years old. We have to get to them early and teach them not to hate each other. That’s my message. And I’m sure there are painters who could do that with paint.

My message is peace. Because I came from a childhood that didn’t have it.

BAIS CHANA, THE REBBE AND ART

RACHELLE: How did Bais Chana have an impact on your or your work?

ESTHER: I had to go to Bais Chana and listen to Rabbi Friedman. And I still see the woman who taught me how to daven with emunah (faith).

We were in California at the time, [Bais Chana] invited me to come. We were making masks, and one of the students had made a mask of my face. It was interesting because masks hide – they’re supposed to cover things up.

After the students made their masks, they decorated them [to express] what they thought they were really like. We talked about who we are personally and what our masks say about us. A lot of times we don’t even have to make that mask, we just are that mask. And you have to work on taking it off. And that’s what Chassidus and Torah does.

ESTHER: I want to make sure that I say this:

What I remembered as a child was how small some of the older men – the jewish men – walked. Including my father. I don’t know if you know what I’m saying by saying walking small… they drew themselves in. Even though they weren’t hiding in their clothing or anything, they just pulled themselves in.

When I came to the United States, I started to learn about the Rebbe and other rabbis and about chassidus. First of all, I tried lots of other places. I went to sweat lodges. I was looking for my G-d.

My father was a frum (observant) Jew, but he had turned away from [religion] because of his experiences. But I could not – because of the Rebbe. When I came to the United States, I saw that people could walk straight and we could be who we are and not be afraid… not make excuses for it. The Rebbe did that for so many of us.

I was lucky enough to see the Rebbe a few times. The last time I saw him, I was in New York for an art exhibition and I saw a lot of German art there. I was playing around with the swastika [in my own art] and I went to the Rebbe, and I said, “Rebbe, when will I stop dealing with the holocaust?” And the Rebbe said, “Good luck with your work.”

That was right before these people from Germany came to invite me to have a show in my hometown. So what was my work? Was my work to make swastikas? Because of what the Rebbe said, I just thought, “How could I do this?” But that was when I knew I just had to speak to the German children… speak to young Germans.

I was talking about how the symbols worked to frighten people. In the end it’s what the Rebbe told me, “Good luck with your work.” And you know, work has to come from all of us… from our connection to goodness, to G-d. To the teachings of our Rebbeim. All these pieces are works of truth.

To see more of Esther’s art: http://www.edithaltman.com/sculpture.html